Juliet du Boulay, Cosmos, Life, and Liturgy in a Greek Orthodox Village (Limni: Denise Harvey, 2009).

Picking up Juliet du Boulay’s Cosmos, Life, and Liturgy (2009) is like stepping into a past made strange. Good and evil spirits inhabit the rivers and streams, marriage is a matter of fate, and a baby’s destiny is written on the lines of its skull soon after it is born. These words on the skull, Du Boulay comments, “once uttered can never be erased.” At first this feels like an old world. The anthropologist speaks for the peasants, always in the passive voice and burying her observations under mountains of structuralist prose. Juliet du Boulay did her fieldwork in Ambeli, Greece, between 1966 and 1968, then went back again from 1970 to 1972, the year when the government built the first road into the village. She went on to write the acclaimed Portrait of a Greek Mountain Village (1974) with its rich and impressionistic portrayals of life in this isolated community. Much of the antiquated feel of Cosmos, Life, and Liturgy comes from fact that the author is writing within a long-dead ethnographic tradition that has faded away for good reason.

Soon after publishing her first book, du Boulay suffered spinal injuries and was unable to work on a book-length study for several decades. She converted to Greek Orthodoxy in the meantime, and grew to love the liturgy and theology of the Eastern Church. In Cosmos, Life, and Liturgy, du Boulay reinterprets her field notes from the 1960s in light of her new-found passion for Orthodox liturgy. The result is beautiful and profound, even if it is not always convincing. “I try to portray the particularities of the villagers’ own images of the sacred while presenting alongside them liturgical material which is universal in Orthodox practice,” she writes. “Of course not every person in such a community embodies this tradition without distortion, and in fact the freedom to make subversive choices is an indispensable part of the process by which each generation of the community learns to live within the whole communal understanding.” This is a theological manifesto for du Boulay as much as an anthropological one. She argues that ancient Christians unified “the divine and natural worlds in a new vision of creation” so profoundly that the divine could be found in every bubbling brook and blade of grass. “From this point of view,” she says, “many western readers may have a sensation that in the cosmos of village Orthodoxy they are coming home to a more ancient Christian understanding.”

Soon after publishing her first book, du Boulay suffered spinal injuries and was unable to work on a book-length study for several decades. She converted to Greek Orthodoxy in the meantime, and grew to love the liturgy and theology of the Eastern Church. In Cosmos, Life, and Liturgy, du Boulay reinterprets her field notes from the 1960s in light of her new-found passion for Orthodox liturgy. The result is beautiful and profound, even if it is not always convincing. “I try to portray the particularities of the villagers’ own images of the sacred while presenting alongside them liturgical material which is universal in Orthodox practice,” she writes. “Of course not every person in such a community embodies this tradition without distortion, and in fact the freedom to make subversive choices is an indispensable part of the process by which each generation of the community learns to live within the whole communal understanding.” This is a theological manifesto for du Boulay as much as an anthropological one. She argues that ancient Christians unified “the divine and natural worlds in a new vision of creation” so profoundly that the divine could be found in every bubbling brook and blade of grass. “From this point of view,” she says, “many western readers may have a sensation that in the cosmos of village Orthodoxy they are coming home to a more ancient Christian understanding.”

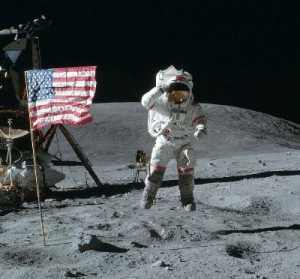

According to du Boulay, Greek Orthodox villagers believe that while He shares the earth with us, the skies are God’s alone to inhabit. When reports about space travel and moon landings reached the village in the early 1970s, people were horrified. Either God would not allow such a desecration of His holy of holies, they reasoned, or else man’s foolhardiness in attempting such an expedition would bring about the end of the world. The sun too is holy. When a baby is about to be born the midwife takes her hands away allowing the child to fall to the earth, for “from dust you came.” Mother and child remain in the house, unwashed, for the first three days of a child’s life and then on the third day the midwife bathes them and brings them out into the sunlight. Although a child might be vulnerable to the Fates for these first days, once the sun’s rays touch it, the baby is truly born. Water is full of spirits as well. In itself water is neither good nor evil, but it is susceptible to spiritual influences of both kinds. Girls must beware of going to the river in case water demons suddenly strike them ill, but water can also have healing properties, which are useful when doctors are expensive and live a long way away.

According to du Boulay, Greek Orthodox villagers believe that while He shares the earth with us, the skies are God’s alone to inhabit. When reports about space travel and moon landings reached the village in the early 1970s, people were horrified. Either God would not allow such a desecration of His holy of holies, they reasoned, or else man’s foolhardiness in attempting such an expedition would bring about the end of the world. The sun too is holy. When a baby is about to be born the midwife takes her hands away allowing the child to fall to the earth, for “from dust you came.” Mother and child remain in the house, unwashed, for the first three days of a child’s life and then on the third day the midwife bathes them and brings them out into the sunlight. Although a child might be vulnerable to the Fates for these first days, once the sun’s rays touch it, the baby is truly born. Water is full of spirits as well. In itself water is neither good nor evil, but it is susceptible to spiritual influences of both kinds. Girls must beware of going to the river in case water demons suddenly strike them ill, but water can also have healing properties, which are useful when doctors are expensive and live a long way away.

The most interesting and innovative parts of this book, however, are not about local superstitions that have already been well documented by others, but about how peasant sensibilities reflect the concerns of the Orthodox liturgy, and vice-versa. Du Boulay writes, for example, that “September and October are months when … the earth is re-born after the summer drought, and it is in explicit analogy with this renewing of the earth that the liturgical year, beginning on 1 September, has as its first major festival, on 8 September, the Birth of the Mother of God. Following this the next great feast is the Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple on 21 November when she is brought as a child for her dedication. Thus when the earth is renewed and young against after the summer, the Mother of God is also in her infancy. And at the end of the agricultural year a similar correspondence is seen, for on 15 August, with the earth falling to rest at the end of the high summer, is celebrated the great festival of the Falling Asleep of the Mother of God.” The centrality of agricultural concerns to the liturgy becomes even more obvious when we see how many botanical metaphors permeate the Akarthistos Hymn to the Mother of God:

The most interesting and innovative parts of this book, however, are not about local superstitions that have already been well documented by others, but about how peasant sensibilities reflect the concerns of the Orthodox liturgy, and vice-versa. Du Boulay writes, for example, that “September and October are months when … the earth is re-born after the summer drought, and it is in explicit analogy with this renewing of the earth that the liturgical year, beginning on 1 September, has as its first major festival, on 8 September, the Birth of the Mother of God. Following this the next great feast is the Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple on 21 November when she is brought as a child for her dedication. Thus when the earth is renewed and young against after the summer, the Mother of God is also in her infancy. And at the end of the agricultural year a similar correspondence is seen, for on 15 August, with the earth falling to rest at the end of the high summer, is celebrated the great festival of the Falling Asleep of the Mother of God.” The centrality of agricultural concerns to the liturgy becomes even more obvious when we see how many botanical metaphors permeate the Akarthistos Hymn to the Mother of God:

Rejoice, branch of an Unfading Sprout:

Rejoice, acquisition of Immortal Fruit!

Rejoice, laborer that laborest for the Lover of mankind:

Rejoice, Thou Who givest birth to the Planter of our life!

Rejoice, cornland yielding a rich crop of mercies:

Rejoice, table bearing a wealth of forgiveness!

Rejoice, Thou Who makest to bloom the garden of delight…

Du Boulay comments, “The link of the Mother of God with the created earth as a whole lies in the action of God being ‘made flesh’, for this flesh which makes Christ man is the common inheritance not only of man but of all creatures; and the relationship goes further, for the flesh which Christ ‘shares in’ derives form the ‘vile clay’ or dust of the earth from which we are made. Thus when God was made flesh it is not only man and the substance of living things that became associated with this action but the fabric of the entire material creation, and it is because of this intimate link between God and the world that creation can be said to be renewed through the Mother of God and the world can be depicted as caught up in rejoicing: ‘When she gave birth in fashion past nature … the whole creation sings.'” I will leave it to the reader to decide how convincing this juxtaposition of liturgy with village spirituality really is, but regardless of whether or not it really reflects a sociological reality, it is certainly an interesting, stimulating, and very beautiful.