The Romanian Orthodox Church expanded significantly after the First World War, establishing new bishoprics, metropolitanates and seminaries. But Neo-Protestantism and schismatic Orthodox movements such as Old Calendarism also grew exponentially during this period, terrifying church leaders who responded by sending missionary priests into the villages to combat sectarianism and schism wherever they found it. Partly in response to initiatives organized by reforming bishops and partly emerging out of new styles of religious reading and practice, several lay renewal movements such as the Lord’s Army and the Stork’s Nest also appeared within the Orthodox Church, implicating large numbers of peasants and workers in tight-knit, rigorous religious communities operating at the margins – and sometimes outside – of Eastern Orthodoxy.

The Romanian Orthodox Church expanded significantly after the First World War, establishing new bishoprics, metropolitanates and seminaries. But Neo-Protestantism and schismatic Orthodox movements such as Old Calendarism also grew exponentially during this period, terrifying church leaders who responded by sending missionary priests into the villages to combat sectarianism and schism wherever they found it. Partly in response to initiatives organized by reforming bishops and partly emerging out of new styles of religious reading and practice, several lay renewal movements such as the Lord’s Army and the Stork’s Nest also appeared within the Orthodox Church, implicating large numbers of peasants and workers in tight-knit, rigorous religious communities operating at the margins – and sometimes outside – of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Bringing the history of the Orthodox Church into an entangled narrative involving sectarianism, heresy, grassroots religious organizing, and nation-building, this book shows how competing religious groups in 1920s Romania responded to and emerged out of similar catalysts, including rising literacy rates, new religious practices, new ways of engaging with Scripture, and a newly empowered laity inspired by universal male suffrage and a growing civil society that was taking control of community organizing. The same nationalist agendas that spawned renewal movements also limited them. Orthodox leaders and missionaries attacked sectarians as ‘un-Romanian’, using the almost hegemonic language of nationalism to police religious groups who were otherwise indifferent to the claims the nation made on their souls. Situated at the intersection of transnational history, religious history, and the history of reading, this book challenges us to rethink the one-sided narratives about modernity and religious conflict in interwar Eastern Europe.

What people are saying:

“Roland Clark has written an extremely thought-provoking book that opens up significant new perspectives on the relationship between Orthodoxy, religious otherness and the state in interwar Romania. Competing ideas of Orthodox renewal, social progress and national salvation, all in the shadow of the phantom threat posed by foreign Repenter sects, are methodically elucidated in this comprehensive study. Drawing on a unique set of archival and contemporary periodical sources that take us into the world of grassroots religious activists, missionaries, dissenters and renewal movements as well as the debates of bishops, theologians and politicians, this book will serve as a trusted guide to the complex world of religious sensibilities and identities, competition and contestation in Romania. This book is a must for all those seeking to understand the dynamics of religious and cultural exchange between East and West in twentieth century Romania and Orthodox Eastern Europe more broadly.”

– James A. Kapaló, University College Cork, author of Inochentism and Orthodox Christianity: Religious Dissent in the Russian and Romanian Borderlands.

“Roland Clark’s study represents a path-breaking analysis of the role played by organized religious faiths in developing an articulated nationalism in 1920s Romania. The author displays a sophisticated use of primary and secondary sources to construct a cogent conceptual framework that invites the reader to reconsider narratives about modernity by also highlighting the significance of universal male suffrage and the growth of civil society. As such, this book offers essential reading for all students of interwar Central and Eastern Europe.”

– Dennis Deletant, Emeritus Professor of Romanian Studies, University College London, UK

“Clark has produced an original work that takes a fresh approach, one that combines several histories that are usually told separately and challenges assumptions about the religiosity of interwar Romania.”

– Grant Harward, H-Nationalism

“Clark’s study offers a well researched, integrated and balanced presentation of inter-war 1920’s religious situation in Romania that is much needed.”

– Sorin Sabou, Jurnal teologic

Reviewed in Balkanistica, Canadian Slavonic Papers, Church History, European Review of History, H-Nationalism, Jurnal teologic, Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Theologia Orthodoxa, Studii si Materiale de Istorie Contemporana, and Observatorul cultural.

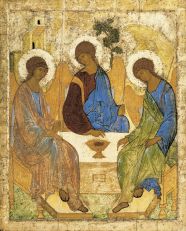

The dogma of the Holy Trinity has always been at the center of Orthodox theology, which is why it was an endless subjection of reflection for Fr. Dumitru Stăniloae, may he rest in peace. The special place that the Trinity occupies in his teaching on the Church makes Fr. Stăniloae the theologian par excellence of the Holy Trinity in the contemporary world. In fact, his entire corpus is a mammoth effort to place the unspeakable mystery of the Holy Trinity at the center of all recent Christian life and thought. As with St. Maximus the Confessor, whose work he has translated and commentated on in Romanian, this dogma does not represent an isolated theme for Fr. Stăniloae. His exegesis of the Trinity glimmer throughout every chapter of his dogmatic theology. While identifying both a united absolute essence and distinct absolute hypostases at the heart of the Holy Trinity, in the most Orthodox spirit Fr. Stăniloae always aimed to bring the living, dynamic personalism of Orthodox Christian theology into the light. Speaking as no one else in contemporary theology has about the infinite value of the person, about its unfathomable depths, and seeing “the undying face of God” in man, Fr. Stăniloae can also speak about the perfect love whose only source is the Holy Trinity.” – From the foreword by His Beatitude Teoctist, Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church

The dogma of the Holy Trinity has always been at the center of Orthodox theology, which is why it was an endless subjection of reflection for Fr. Dumitru Stăniloae, may he rest in peace. The special place that the Trinity occupies in his teaching on the Church makes Fr. Stăniloae the theologian par excellence of the Holy Trinity in the contemporary world. In fact, his entire corpus is a mammoth effort to place the unspeakable mystery of the Holy Trinity at the center of all recent Christian life and thought. As with St. Maximus the Confessor, whose work he has translated and commentated on in Romanian, this dogma does not represent an isolated theme for Fr. Stăniloae. His exegesis of the Trinity glimmer throughout every chapter of his dogmatic theology. While identifying both a united absolute essence and distinct absolute hypostases at the heart of the Holy Trinity, in the most Orthodox spirit Fr. Stăniloae always aimed to bring the living, dynamic personalism of Orthodox Christian theology into the light. Speaking as no one else in contemporary theology has about the infinite value of the person, about its unfathomable depths, and seeing “the undying face of God” in man, Fr. Stăniloae can also speak about the perfect love whose only source is the Holy Trinity.” – From the foreword by His Beatitude Teoctist, Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church

Fr. Stăniloae (1903-1993) is widely considered as one of the greatest Orthodox theologians of the twentieth century. He was Professor of Dogmatics at the Theological Institute in Bucharest, Romania, from 1947 to 1973. In 1990 he was made a Member of the Romanian Academy.

Vasilica Barbu, also known as Mother Veronica, a seer and then an abbess in mid-twentieth century Romania, had visions of Jesus, Mary, and a variety of angels and saints, beginning in 1937. Supported by her parish priest and other local believers, she published an account of her visions and founded a convent for adolescent girls. The Vladimireşti convent proved to be very successful, but the Securitate (secret police) decided to close it down on the grounds that it was harbouring fascist fugitives. A close reading of how Barbu navigated the challenges of poverty, patriarchy, and the rise of state socialism reveals not only a story of incredible tenacity in the face of adversity but also how fundamentally religious values changed following the Second World War. Whereas in the late 1930s Barbu’s visions enabled her to bring together a strong community of supporters and to attract the attention of the most powerful men in the country, in the early 1950s both Church leaders and the Securitate attacked “mysticism” as heterodox and socially deviant.

Vasilica Barbu, also known as Mother Veronica, a seer and then an abbess in mid-twentieth century Romania, had visions of Jesus, Mary, and a variety of angels and saints, beginning in 1937. Supported by her parish priest and other local believers, she published an account of her visions and founded a convent for adolescent girls. The Vladimireşti convent proved to be very successful, but the Securitate (secret police) decided to close it down on the grounds that it was harbouring fascist fugitives. A close reading of how Barbu navigated the challenges of poverty, patriarchy, and the rise of state socialism reveals not only a story of incredible tenacity in the face of adversity but also how fundamentally religious values changed following the Second World War. Whereas in the late 1930s Barbu’s visions enabled her to bring together a strong community of supporters and to attract the attention of the most powerful men in the country, in the early 1950s both Church leaders and the Securitate attacked “mysticism” as heterodox and socially deviant.

Three entries in the Hidden Galleries Digital Archive:

Vasile Popa, The Miracles of Maglavit: The Man Who Spoke With God (1935)

Petrache Lupu: The Miracle of Maglavit (1935)

On the Legionary Organization: Mysticism, Massacres, Betrayal, vols. 1 & 2, Romania, (1964)

These booklets appear in a Romanian General Directorate of Police file from September 1935, having been confiscated almost immediately after they were published. By this time hundreds of thousands of pilgrims had begun to descend on the small village of Maglavit, causing the authorities to take an interest in published reports about what was happening there. A shepherd from the small village of Maglavit near the Bulgarian border, Lupu described several visions he had had of God while he was watching his sheep in May and June that year. Despite apparently having a speech defect – some sources say he was almost mute – he began calling people to repent, telling his listeners to not to raise their hands against the weak, not to steal, and not to deceive. His village quickly became a pilgrimage site attracting so many people that, according to this author, there was not even a tiny corner where one could stay.

These booklets appear in a Romanian General Directorate of Police file from September 1935, having been confiscated almost immediately after they were published. By this time hundreds of thousands of pilgrims had begun to descend on the small village of Maglavit, causing the authorities to take an interest in published reports about what was happening there. A shepherd from the small village of Maglavit near the Bulgarian border, Lupu described several visions he had had of God while he was watching his sheep in May and June that year. Despite apparently having a speech defect – some sources say he was almost mute – he began calling people to repent, telling his listeners to not to raise their hands against the weak, not to steal, and not to deceive. His village quickly became a pilgrimage site attracting so many people that, according to this author, there was not even a tiny corner where one could stay.

Feeling threatened by the sudden popularity of neo‑Protestantism in Romania and equipped with new church‑building strategies by their studies abroad, in the early twentieth century leaders of the Romanian Orthodox Church promoted regular Bible study, Christian social activism, and increased piety as a way of renewing Orthodox spirituality. After the First World War, two of their students, Teodor Popescu and Dumitru Cornilescu, led a revival at St Ştefan’s Church in Bucharest, colloquially referred to as The Stork’s Nest. This article examines the schism that emerged between the revivalist preachers and their former teachers and mentors. Both sides developed opposing viewpoints on the authority of the Bible, the usefulness of Cornilescu’s Biblical translation, the role of the saints and the Virgin Mary, prayers for the dead, and the role of the Church in salvation. Popescu’s opponents turned him out of the Orthodox Church after it was discovered that he had changed the liturgy, and a new community of believers was born, known as “Tudorists”, or “Christians According to the Scriptures”.

Feeling threatened by the sudden popularity of neo‑Protestantism in Romania and equipped with new church‑building strategies by their studies abroad, in the early twentieth century leaders of the Romanian Orthodox Church promoted regular Bible study, Christian social activism, and increased piety as a way of renewing Orthodox spirituality. After the First World War, two of their students, Teodor Popescu and Dumitru Cornilescu, led a revival at St Ştefan’s Church in Bucharest, colloquially referred to as The Stork’s Nest. This article examines the schism that emerged between the revivalist preachers and their former teachers and mentors. Both sides developed opposing viewpoints on the authority of the Bible, the usefulness of Cornilescu’s Biblical translation, the role of the saints and the Virgin Mary, prayers for the dead, and the role of the Church in salvation. Popescu’s opponents turned him out of the Orthodox Church after it was discovered that he had changed the liturgy, and a new community of believers was born, known as “Tudorists”, or “Christians According to the Scriptures”.

The first two parts of “The Unbelieved” argued for the possibility of the existence of supernatural beings and for their agency in historical writing. This instalment is a roundtable assessing the problems and potential in the category of the Unbelieved and in its knowability. Space limitations prevented our following the rich avenues of further inquiry our extraordinary peer reviewers suggested, but we remain grateful, especially for their reminders of the complexity of motivations of historians who avoid the Unbelieved and their emphasis on the importance of humility as a historian’s tool.

The first two parts of “The Unbelieved” argued for the possibility of the existence of supernatural beings and for their agency in historical writing. This instalment is a roundtable assessing the problems and potential in the category of the Unbelieved and in its knowability. Space limitations prevented our following the rich avenues of further inquiry our extraordinary peer reviewers suggested, but we remain grateful, especially for their reminders of the complexity of motivations of historians who avoid the Unbelieved and their emphasis on the importance of humility as a historian’s tool.

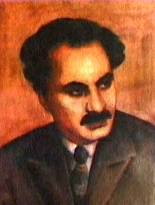

This article examines ideas about human personhood, the Church, and ecumenicism in the thought of the Romanian theologian Dumitru Stăniloae (1903-1993). It argues that Stăniloae developed his thinking on these issues during two different periods of his life. His interwar writings discuss the debates in nationalist terms, while those works written in the 1970s and 1980s describe Christian unity through a Trinitarian framework. Despite the extremely different logic behind them, Stăniloae’s two ecclesial models are remarkably similar. In order to emphasize how profoundly historical context has shaped Orthodox thinking about the Church, the article briefly compares Stăniloae’s work to that of Nikolai Afanasiev, Vladimir Lossky, and John Zizioulas, three Orthodox theologians who wrote extensively about ecclesiology and ecumenicism.

This article examines ideas about human personhood, the Church, and ecumenicism in the thought of the Romanian theologian Dumitru Stăniloae (1903-1993). It argues that Stăniloae developed his thinking on these issues during two different periods of his life. His interwar writings discuss the debates in nationalist terms, while those works written in the 1970s and 1980s describe Christian unity through a Trinitarian framework. Despite the extremely different logic behind them, Stăniloae’s two ecclesial models are remarkably similar. In order to emphasize how profoundly historical context has shaped Orthodox thinking about the Church, the article briefly compares Stăniloae’s work to that of Nikolai Afanasiev, Vladimir Lossky, and John Zizioulas, three Orthodox theologians who wrote extensively about ecclesiology and ecumenicism.

This article uses the early career of Nichifor Crainic (1889–1972) to show why Orthodox Christianity became a central element of Romanian ultranationalism during the 1920s. Most Romanian nationalists were atheists prior to the First World War, but state-sponsored nation-building efforts catalyzed by territorial expansion and the incorporation of ethnic and religious minorities allowed individuals such as Crainic to introduce religious nationalism into the public sphere. Examining Crainic’s work during the 1920s shows how his nationalism was shaped by mainstream political and ideological currents, including state institutions such as the Royal Foundations of Prince Carol and the Ministry of Cults and of Art. Despite championing “tradition,” Crainic was committed to changing Romanian society so long as that change followed autochthonous Romanian models. State sponsorship allowed Crainic to promote religious nationalism through his periodical Gândirea. Crainic’s literary achievements earned him a chair in theology, from which he pioneered new ways of thinking about mysticism as an expression of Romanian culture and as crucial to understanding the Romanian nation.

This article uses the early career of Nichifor Crainic (1889–1972) to show why Orthodox Christianity became a central element of Romanian ultranationalism during the 1920s. Most Romanian nationalists were atheists prior to the First World War, but state-sponsored nation-building efforts catalyzed by territorial expansion and the incorporation of ethnic and religious minorities allowed individuals such as Crainic to introduce religious nationalism into the public sphere. Examining Crainic’s work during the 1920s shows how his nationalism was shaped by mainstream political and ideological currents, including state institutions such as the Royal Foundations of Prince Carol and the Ministry of Cults and of Art. Despite championing “tradition,” Crainic was committed to changing Romanian society so long as that change followed autochthonous Romanian models. State sponsorship allowed Crainic to promote religious nationalism through his periodical Gândirea. Crainic’s literary achievements earned him a chair in theology, from which he pioneered new ways of thinking about mysticism as an expression of Romanian culture and as crucial to understanding the Romanian nation.

This article explores the interplay of religion, antisemitism, and personal rivalries in building the ultra-nationalist movement in 1930s Romania, using the career of Nichifor Crainic as a case study. As a theologian, Crainic created and taught a synthesis of nationalism and Romanian Orthodoxy which was broadly accepted by most ultranationalists in interwar Romania. As a journalist, Crainic directed several newspapers which spearheaded acrimonious attacks on democratic and ultranationalist politicians alike. As a politician, he joined and left both Corneliu Zelea Codreanu’s Legion of the Archangel Michael and A.C. Cuza’s National Christian Defense League before attempting to form his own Christian Workers’ Party. Crainic’s writings ultimately earned him a place as a minister in two governments and membership of the Romanian Academy. His career reveals an ultranationalist movement rife with division and bickering but united around a vaguely defined ideology of religious nationalism, xenophobia, and antisemitism.

This article explores the interplay of religion, antisemitism, and personal rivalries in building the ultra-nationalist movement in 1930s Romania, using the career of Nichifor Crainic as a case study. As a theologian, Crainic created and taught a synthesis of nationalism and Romanian Orthodoxy which was broadly accepted by most ultranationalists in interwar Romania. As a journalist, Crainic directed several newspapers which spearheaded acrimonious attacks on democratic and ultranationalist politicians alike. As a politician, he joined and left both Corneliu Zelea Codreanu’s Legion of the Archangel Michael and A.C. Cuza’s National Christian Defense League before attempting to form his own Christian Workers’ Party. Crainic’s writings ultimately earned him a place as a minister in two governments and membership of the Romanian Academy. His career reveals an ultranationalist movement rife with division and bickering but united around a vaguely defined ideology of religious nationalism, xenophobia, and antisemitism.

Self-understandings of Romania as a mid-point between Orient and Occident shaped both the Orthodoxist rejection of internationalism and their alternative models of transnational cooperation. Unlike expansionist Russian Slavophile messianism, which was confident of Russia’s place as a world power, Orthodoxist Romanians felt themselves to be a “minor” nation, always on the periphery. Fulfilling their manifest destiny, therefore, required transnational co-operation. They had already rejected the “internationalist” models of Western Europe, but pan-Balkan and/or pan-Orthodox solutions offered a way to build international ties without abandoning their ‘Oriental’ exceptionalism.

Self-understandings of Romania as a mid-point between Orient and Occident shaped both the Orthodoxist rejection of internationalism and their alternative models of transnational cooperation. Unlike expansionist Russian Slavophile messianism, which was confident of Russia’s place as a world power, Orthodoxist Romanians felt themselves to be a “minor” nation, always on the periphery. Fulfilling their manifest destiny, therefore, required transnational co-operation. They had already rejected the “internationalist” models of Western Europe, but pan-Balkan and/or pan-Orthodox solutions offered a way to build international ties without abandoning their ‘Oriental’ exceptionalism.

Scholarship on Christian mysticism underwent a renaissance in Romania between 1920 and 1947, having a lasting impact on the way that Romanian theologians and scholars think about Romanian Orthodoxy Christianity in general, and mysticism in particular. Fascist and ultra-nationalist political and intellectual currents also exploded into the Romanian public sphere at this time. Many of the same people who were writing mystical theology were also involved with ultra-nationalist politics, either as distant sympathizers or as active participants. This paper situates the early work of the renowned theologian Dumitru Stăniloae within the context of mystical fascism, nationalist apologetics, and theological pedagogy in which it was originally produced. It shows how a new academic discipline formed within an increasingly extremist political climate by analyzing the writings of six key men whose work significantly shaped Romanian attitudes towards mysticism: Nae Ionescu, Mircea Eliade, Lucian Blaga, Nichifor Crainic, Ioan Gh. Savin, and Dumitru Stăniloae. The contributions of these thinkers to Romanian theology are not dismissed once their nationalism is noted, but they are contextualized in a way that allows twenty-first century thinkers to move beyond the limitations of these men and into fresh ways of thinking about the divine-human encounter.

Scholarship on Christian mysticism underwent a renaissance in Romania between 1920 and 1947, having a lasting impact on the way that Romanian theologians and scholars think about Romanian Orthodoxy Christianity in general, and mysticism in particular. Fascist and ultra-nationalist political and intellectual currents also exploded into the Romanian public sphere at this time. Many of the same people who were writing mystical theology were also involved with ultra-nationalist politics, either as distant sympathizers or as active participants. This paper situates the early work of the renowned theologian Dumitru Stăniloae within the context of mystical fascism, nationalist apologetics, and theological pedagogy in which it was originally produced. It shows how a new academic discipline formed within an increasingly extremist political climate by analyzing the writings of six key men whose work significantly shaped Romanian attitudes towards mysticism: Nae Ionescu, Mircea Eliade, Lucian Blaga, Nichifor Crainic, Ioan Gh. Savin, and Dumitru Stăniloae. The contributions of these thinkers to Romanian theology are not dismissed once their nationalism is noted, but they are contextualized in a way that allows twenty-first century thinkers to move beyond the limitations of these men and into fresh ways of thinking about the divine-human encounter.

This article is about an appropriation that did not happen, of an as yet unformed Russian tradition, by men who did not read Russian. The cultural movement known as Romanian Orthodoxism exhibited many of the trademarks of Russian symbolism and of the religious, Slavophile disciples of Vladimir Soloviev. It emerged in the early 1920s and continued to grow in popularity until the end of the Second World War. Although strong similarities existed between Romanian Orthodoxists and some Silver Age Russian intellectuals, the former were diffident about acknowledging any debt to the Russians, even while they eagerly recognized intellectual debts from elsewhere in the world.

This article is about an appropriation that did not happen, of an as yet unformed Russian tradition, by men who did not read Russian. The cultural movement known as Romanian Orthodoxism exhibited many of the trademarks of Russian symbolism and of the religious, Slavophile disciples of Vladimir Soloviev. It emerged in the early 1920s and continued to grow in popularity until the end of the Second World War. Although strong similarities existed between Romanian Orthodoxists and some Silver Age Russian intellectuals, the former were diffident about acknowledging any debt to the Russians, even while they eagerly recognized intellectual debts from elsewhere in the world.

Roland Clark. ‘Lev Shestov and the Crisis of Modernity,’ Arhaeus, 11-12, (2007-08): 233-248.

One of the most unique of the Russian religious philosophers who populated first the salons of St. Petersburg and then the émigré gatherings in Berlin and Paris, Lev Shestov (1866-1938) is also one of the most difficult to force into a strict philosophical system. Learning from Nietzsche that God was dead, and that therefore there could be no idea of progress, no meaning in suffering, and no reference outside of the self, between 1897 and 1911 Shestov sought to understand how live as an individual – as an egoist. This stance brought him into contact, both intellectually and personally, with many of the leading figures of European Modernism because his pessimistic worldview found so many similarities with their own.

One of the most unique of the Russian religious philosophers who populated first the salons of St. Petersburg and then the émigré gatherings in Berlin and Paris, Lev Shestov (1866-1938) is also one of the most difficult to force into a strict philosophical system. Learning from Nietzsche that God was dead, and that therefore there could be no idea of progress, no meaning in suffering, and no reference outside of the self, between 1897 and 1911 Shestov sought to understand how live as an individual – as an egoist. This stance brought him into contact, both intellectually and personally, with many of the leading figures of European Modernism because his pessimistic worldview found so many similarities with their own.

Roland Clark. “The Dark Side in Milton and Njegoš,” Sydney Studies in Religion, 6/1 (2004): 102-119.

“A spark, lost deep in earthly dust,” the Montenegrin poet/Prince/Bishop is led by a ray – his own immortal “bright idea” – out of the dark world of “thick gloom” through the seven heavens into the “region of light”, where he is shown the mysteries of the pre-creation cataclysm from which God derived his omnipotence, and of the Fall of men and of angels. Petar Petrović Njegoš (c.1813-1851), author of the Luča Mikrokozma (Ray of the Microcosm), an epic poem that remains quintessentially Slavic despite reflecting strongly occidental influences such as Dante, Milton and Kant, expounds to his readers throughout his narrative a religious dualism that reveals the endurance of Zoroastrianism, Origenism, Bogomilism and Slavic folk legends, as well as Njegoš’s own highly original philosophical speculations. Through a comparison with Milton’s famous epic, Paradise Lost, this paper seeks to shed new light on Njegoš’s religious philosophy as he struggles with the problem of evil and the overwhelming presence of ‘the dark side’ in his troubled mountain kingdom of Montenegro. Among other things, Njegoš’s poem highlights the power of Shelley’s thesis of the usurping tyrant-God in Milton, as well as the difficulties in explaining matter and the ‘nothing’ outside of God when positing an ex deo creation, as both poets do.

“A spark, lost deep in earthly dust,” the Montenegrin poet/Prince/Bishop is led by a ray – his own immortal “bright idea” – out of the dark world of “thick gloom” through the seven heavens into the “region of light”, where he is shown the mysteries of the pre-creation cataclysm from which God derived his omnipotence, and of the Fall of men and of angels. Petar Petrović Njegoš (c.1813-1851), author of the Luča Mikrokozma (Ray of the Microcosm), an epic poem that remains quintessentially Slavic despite reflecting strongly occidental influences such as Dante, Milton and Kant, expounds to his readers throughout his narrative a religious dualism that reveals the endurance of Zoroastrianism, Origenism, Bogomilism and Slavic folk legends, as well as Njegoš’s own highly original philosophical speculations. Through a comparison with Milton’s famous epic, Paradise Lost, this paper seeks to shed new light on Njegoš’s religious philosophy as he struggles with the problem of evil and the overwhelming presence of ‘the dark side’ in his troubled mountain kingdom of Montenegro. Among other things, Njegoš’s poem highlights the power of Shelley’s thesis of the usurping tyrant-God in Milton, as well as the difficulties in explaining matter and the ‘nothing’ outside of God when positing an ex deo creation, as both poets do.

asdasda

Roland Clark. “Did Baptism Change the Rus’?” Phronema, 18, (2003): 91-108.

Robin Horton’s study of African conversion led him to conclude that ‘African responses to the world religions … are responses which, given the appropriate economic and social background conditions, would most likely have occurred in some recognizable form even in the absence of the world religions.’ Examining the ‘Baptism of Rus’’ in 988, one discovers social changes occurring alongside religious conversion and a political environment in which a turn towards monotheistic universalism appears the ‘natural’ progression, but baptism transformed Russian society in numerous and unexpected ways. As well as unifying diverse peoples, encouraging trade and heralding a new era in international relations, official conversion introduced a new clerical class, liturgy, centralized worship, and new conceptions of time, transforming the legal system, kingship structures, art, music, architecture, burial practices and education. This article argues that social changes were channeled in very new directions that were not necessarily ‘in the air’ anyway.

Robin Horton’s study of African conversion led him to conclude that ‘African responses to the world religions … are responses which, given the appropriate economic and social background conditions, would most likely have occurred in some recognizable form even in the absence of the world religions.’ Examining the ‘Baptism of Rus’’ in 988, one discovers social changes occurring alongside religious conversion and a political environment in which a turn towards monotheistic universalism appears the ‘natural’ progression, but baptism transformed Russian society in numerous and unexpected ways. As well as unifying diverse peoples, encouraging trade and heralding a new era in international relations, official conversion introduced a new clerical class, liturgy, centralized worship, and new conceptions of time, transforming the legal system, kingship structures, art, music, architecture, burial practices and education. This article argues that social changes were channeled in very new directions that were not necessarily ‘in the air’ anyway.